Situated on the southeastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula, Oman has one of the longest histories of any Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) state.

A journey back in time to the 16th century

Oman’s balancing act

Thanks to its location on the trade routes between east and west, Oman has centuries of experience balancing great powers — whether Turkish, Portuguese, British, Persian or Saudi — against one another to preserve its unique identity and independence. Its small size and relatively small resource base in comparison to its Saudi and Emirati neighbors have provided Muscat with a moderately sized economy. That may limit Oman’s ambitions, but it has also endowed it with just enough wealth to maintain its social contract.

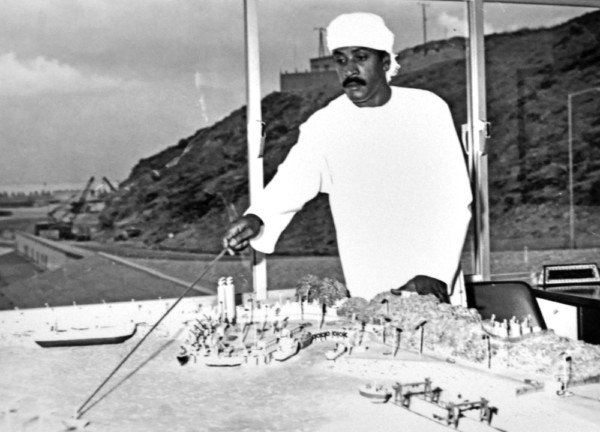

Sultan Qaboos bin Said, the reigning monarch since 1970, took the throne just as the United Kingdom exited the Persian Gulf. His early years saw him battle communist rebels in the Dhofar Rebellion of 1962-75, and he worked assiduously to unify, both physically and politically, Oman’s restive interior provinces with its more cosmopolitan coast. As a result of the sultan’s experiences, Oman became risk-averse and focused on stability. Muscat, accordingly, has refrained from picking sides as often as possible — a stance that has enabled the sultanate to become a useful interlocutor among Saudi Arabia, Iran and the United States.

The costs of neutrality

The country’s overall commitment to neutrality has, however, meant keeping its Arab neighbors at arm’s length — to the particular chagrin of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Oman has consistently hampered Saudi-Emirati efforts to create a tighter GCC and even killed a 2013 proposal to symbolically become part of a Gulf Union. Muscat also refused to join its more powerful Gulf neighbors in imposing a blockade on Doha last year, choosing instead to retain its links with Qatar and maintain its healthy trade and diplomatic relationship with Iran.

Saudi and Emirati officials have also accused Muscat of giving too much influence to Yemen’s Houthis, even as Oman uses its contacts with the rebel group to facilitate negotiations between them and a Saudi-led coalition seeking to reinstall the Red Sea state’s ousted government. Oman and the United Arab Emirates are also competing for influence in Yemen’s eastern al-Mahrah governorate, which was an exclusively Omani sphere of influence prior to the Emirati intervention in the current Yemeni civil war.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates want Oman to ideally halt trade with Iran, shut down smuggling routes to Yemen’s Houthis, pressure Qatar, and help bring the other Gulf states to heel.

Bringing weight to bear on Oman

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi desire a Muscat that is more pliable to their regional interests on a variety of issues. For the two regional powers, Oman should display more willingness to halt trade with Iran, shut down smuggling routes to the Houthis, exert pressure on Qatar, and participate in their efforts to bring the other Gulf states to heel. To do so, the pair have a variety of means at their disposal, including the ability to rattle Muscat’s relationship with the United States. Thanks to their increased influence in the current White House, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi could try to convince Washington that Muscat is the weak link in the United States’ anti-Iran regional strategy because the country allows Houthi arms to traverse its soil and Iran to circumvent sanctions and blockades. They could also raise questions about Oman’s loyalty to U.S. regional goals while simultaneously intimating to Muscat that Washington could take sanctions against Omani businesses, individuals or officials who fail to cooperate with the anti-Iran strategy.

But should the America angle fall flat — as it largely has with Qatar — Saudi Arabia and the UAE have other options. Abu Dhabi could pressure Omani citizens and businesses, both within the United Arab Emirates itself, Oman’s largest trading partner, and along its border. This light harassment could include a slower distribution of visas, longer waits at the border and intrusive inspections of Omani businesses in the United Arab Emirates. Omanis working for the Emirati government could also find themselves suddenly unemployed, as the Emiratis have previously used summary layoffs as a means of expressing political displeasure with particular governments.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also have other tools at their disposal. In addition to establishing an investment fund for the sultanate, the Saudis have invested $210 million in Oman’s flagship port project at Duqm, while the Emiratis have invested in Omani ports at Sohar and Salalah. To alter Oman’s behavior, the two Gulf powers could pare back investment or delay cash transfers. Conversely, the two could also add more investment funds as a ploy to bring Muscat into line.

Finally, there could be attempts to influence the succession process of the sultan himself. With Sultan Qaboos reportedly in poor health amid a lack of clarity about the transfer of power (rumors suggest that two sealed envelopes, one in Muscat and one in Salalah, hold the names of the successor), Riyadh and Abu Dhabi could utilize their intelligence services and connections with the royal court to influence the succession process. With a shortlist of successors already publicly known, the two could signal who is acceptable and who is not, thereby enabling them to implicitly threaten rewards and punishments for the royal family. Members of the family could ignore such machinations, but in doing so, they would risk appointing a leader who would become the target of Oman’s two biggest neighbors.

Oman might not be as vulnerable as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates hope.